Jill LePore’s New Yorker polemic “The Disruption Machine” attempts to debunk the incredibly popular Innovator’s Dilemma, a theory written by HBS professor Clayton Christensen. I’ve been reading the debate around it with some interest. It’s becoming a really interesting conversation but I think the debate is focused on the wrong thing - whether or not these ideas are absolutely correct, even axiomatic. They aren’t always true. But that doesn’t mean these concepts are useless. Quite the opposite.

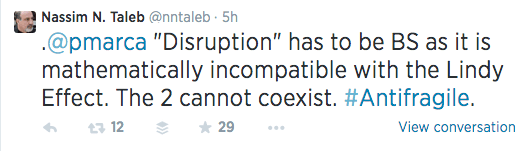

This morning, Nassim Taleb introduced a second idea into the debate when he wrote to Marc Andreessen:

The Lindy Effect is an idea credited to Albert Goldman and says “the future career expectations of a television comedian is proportional to the total amount of his past exposure on the medium.” In his book Antifragile, Taleb expands this theory to all of human development. Taleb summarized his view on the theory in an op-ed titled “The Surprising Truth: Technology is Aging in Reverse,” published in Wired in 2012.

While Taleb’s Wired Op-Ed explains the Lindy Effect, it struggles to apply it broadly:

But what about a technology that we currently see as inefficient and dying, like print newspapers, land lines, or physical storage for tax receipts? People often counter my argument by presenting such examples. To which I respond: The Lindy Effect is not about every technology, but about life expectancy — which is simply a probabilistically derived average.

The first challenge with both the Lindy Effect and the Innovator’s Dilemma is neither are predictive, as Taleb says above. Neither Taleb nor Christensen maintains a list of the industries or companies likely to be disrupted, for example. Both theories are great descriptive tools for describing history, but not predicting the future.

The second challenge is that both are theories supported by selective examples. Christensen’s examples are, in large part, undermined by LePore’s research. The Lindy Effect works until it doesn’t. The paper book will continue to flourish until the point the ebook takes over. Same with ceramic plates.

Despite those flaws, both theories are incredibly useful as frameworks to describe industry dynamics. The entire freemium world is predicated on Christensen’s Innovators Dilemma. Enterprise incumbents, constrained by large costs-of-customer-acquisition, can’t compete with startups who acquire customers for near-free, harkening Christensen’s mini-mill analogy. The Lindy Effect describes the decision-making inertia captured in the aphorism “no one gets fired for buying IBM.” With one phrase, a founder can summarize the competitive dynamics within an industry.

Disruption will happen in certain sectors and long-incumbent technologies will continue to prevail in others. In some sense, these are the main forces in tension in most sectors. While these neither theories apply to every industry nor every set of companies competing with each other, they are useful descriptive frameworks for talking about industry dynamics, despite their flaws.