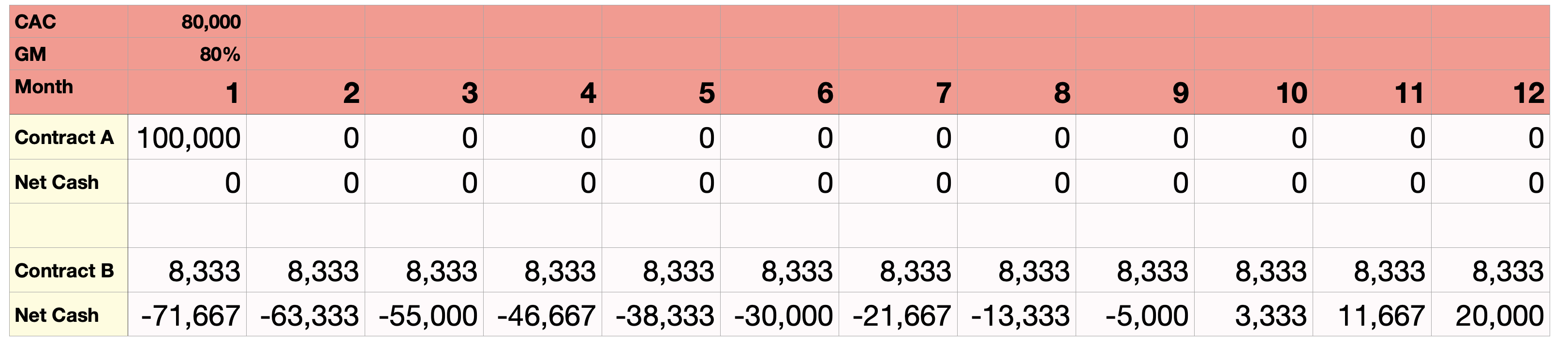

Imagine an AE closes two contracts for $100k ARR. The contracts are identical twelve month contracts except for the payment terms.

Contract A requires annual prepayment - all the cash will be paid tomorrow. Contract B relaxes payment terms to monthly payment, 12 monthly installments for the next year.

Is the payback period for each contract the same?

On one hand, I could plug the numbers into the formula blindly and reply yes, they are identical.

But the contracts are substantially different to the company.

Contract A pays for itself today. Said otherwise, Contract A has a payback period of 0 days. All of the sales and marketing dollars invested to obtain persuade the buyer to put digital ink to pdf have been recouped immediately.

One couldn’t assert the same for contract B, which takes 10 months in our hypothetical example. For a company with a longer payback, the payback period implicitly assumes a successful renewal to achieve the same positive effect on the company balance sheet.

The payback period metric doesn’t capture the difference in the quality of the revenue/cash collections. That may seem like a distinction without a difference but the distinction is an important difference.

A startup closing only Contract As will be far more capital efficient than one capturing Contract Bs. Contract As don’t require burning equity dollars to hire more AEs; the company reinvests customer revenue dollars to scale.

Let’s take this idea time scale further out: multi-year deals. A multi-year prepay offers even greater benefit to a software company. It’s an interest-free loan from a customer to grow the GTM team.

For example, if a three-year contract is discounted the startup’s cost of capital for borrowing is simply the discount amortized over the contract period (eg, 10% over three years or 3.2% per year which incidentally costs less than venture debt). And the company has two years of marginal profit to invest in the GTM.

Most startups today prefer to run their sales teams on annual deals to accelerate sales cycles and minimize the risk of clawing back commissions on multi-year deals that churn at some point in the service period.

But there is a viable GTM strategy for startups to book multi-year deals with pre-payment, and use that cash to finance GTM growth. Especially if logo churn is low, account expansion is strong, and the sales cycles are brief.

Cash collections ought to be considered when calculating the payback period. After all, the point of the payback period metric is to determine when to invest more in sales and marketing. If an account executive can recoup all the cost of customer acquisition immediately, shouldn’t the startup collect those dollars and hire another AE?

Today, investors (myself included) use payback period as an efficiency yardstick to compare the relative efficiency of GTM spend from one company to the next. It’s also useful to understand how much risk is involved with payback periods of longer than a year.

That’s a useful tool. But it’s divorced from the original purpose of the payback period of determining when to double down on scaling a GTM team.

It’s time for two metrics to exist: a cash-flow based months-to-repay and an accrual accounting metric.