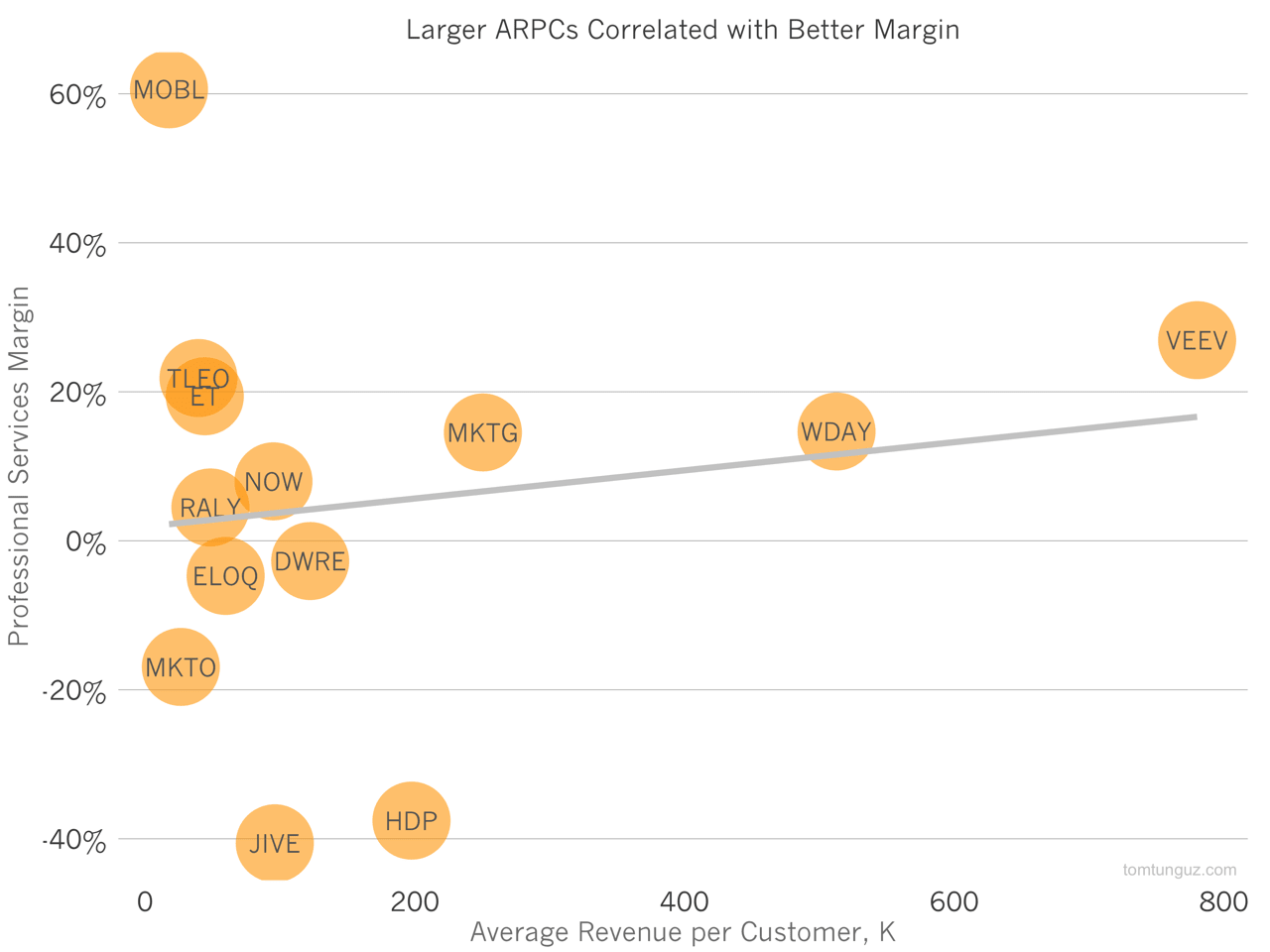

As the next generation of SaaS companies achieve maturity, they have begun to serve larger and larger customers, who in addition to demanding a great product, often request services. Professional services, as they are often called, entail training and customization. For product driven startups, the decision to offer professional services is a tricky one. On one hand, the customer is always right and services often enable substantially larger contracts. On the other hand, selling hours to drive revenue decreases the efficiency of the business, by hiring more people in order to grow revenue linearly. In addition, many businesses operate their services divisions at a loss. But not all. The chart above compares the gross margins on professional services across the 13 publicly traded SaaS with the largest average revenue per customer, which ranges from $50-$800K for the 2015 fiscal year where available, and otherwise the last disclosed year before acquisition.

Some of these companies generate upwards of 30% of their revenue from professional services. So, the profitability of this unit impacts the overall profitability of the business.

While Jive and Hortonworks lose about forty cents per dollar of professional services, the negative gross margin contingent constitutes the minority in this data set.

There is an outlier: MobileIron generates 61% gross margin on services, which is close to their software margin (81%), and closer still to the median across public traded software companies of 70%. This is because MobileIron offers both licenses and software subscriptions. The annual support contracts for the licenses bump up the gross margin quite a bit. So it’s not quite apples to apples.

The remaining gross margin positive companies tend to operate their professional services teams at somewhere between 15 to 25 points of margin.

The greater the fraction revenue from professional services, the larger the gross margins tend to be. Again, this is likely because of the substantial influence over the overall economics of the business. If the professional services team represents 30% of revenue and is operating at a negative margin, then the overall margins of the business suffer greatly. Hortonworks, in the bottom right, is an outlier – though, I suspect this is a deliberate strategy to win share in a competitive market with a commodity open source product.

Typically, larger average revenue per customer contracts enable better margins. This is logical. If a customer spends $500,000 per year on software, the marginal cost of $150k in services in order to make sure the deployment succeeds seems like a relatively cheap insurance policy, even at high margin. After all, there is an internal champion who pushed the purchasing decision through procurement, and is, for all intents and purposes, pot committed to ensuring success. On the other hand, the stakes aren’t so large for a $20,000 per year product. Consequently the willingness to pay for professional services diminishes as a function of price point. Again, MobileIron is an outlier because of its license software business.

The decision to offer professional services shouldn’t be taken lightly. It requires staffing a new team, crafting an offering to customers, and modeling the financial impact to the business. The data suggests that customers are willing to pay 20%+ margins on price points of greater than $200,000. Less than that price point, the data shows it to be difficult to operate a professional services team at better than breakeven.