This post is part of a continuing series evaluating the S-1s of publicly traded SaaS companies in order to better understand the core business and build a library of benchmarks that might be useful to founders.

All of the businesses we’ve looked at in the past have been purely SaaS businesses. Today, we’ll examine Tableau, the market leader for data visualization software. Tableau sells software the old-fashioned way, with perpetual licenses not subscriptions. Customers pay a fee for the software up-front, in addition to an annual maintenance fee of about 20-25%. To offset the mostly one-time payment from customers, Tableau employs a land-and-expand strategy. The company went public in 2013 and we’ll use data from their S-1 through 2013 to benchmark the business.

Tableau sells their desktop client to one or two data analysts within a company. Many times, these first analysts download the product on the web and convert to paid with a credit card. Over time, colleagues within the company see the software and purchase it for themselves. Sometimes, teams buy a Tableau server license to collaborate internally on data analysis. When enough employees of a company use Tableau, the company is able to sell an enterprise-wide license, but these very large transactions are still quite few in number. Tableau closed 179 transactions of greater than $100k ACVs in the first quarter of the year up from 80 three quarters before.

In the next seven charts, we’ll explore how Tableau built their business. We will explore revenue growth, average revenue per customer, sales efficiency, payback periods, net income, gross margin and engineering spending. In these plots, I’ve used Tableau’s colors as a consistent legend. Tableau company data is blue, median values are black, and other company values from a basket of about 40 publicly traded SaaS companies are gray.

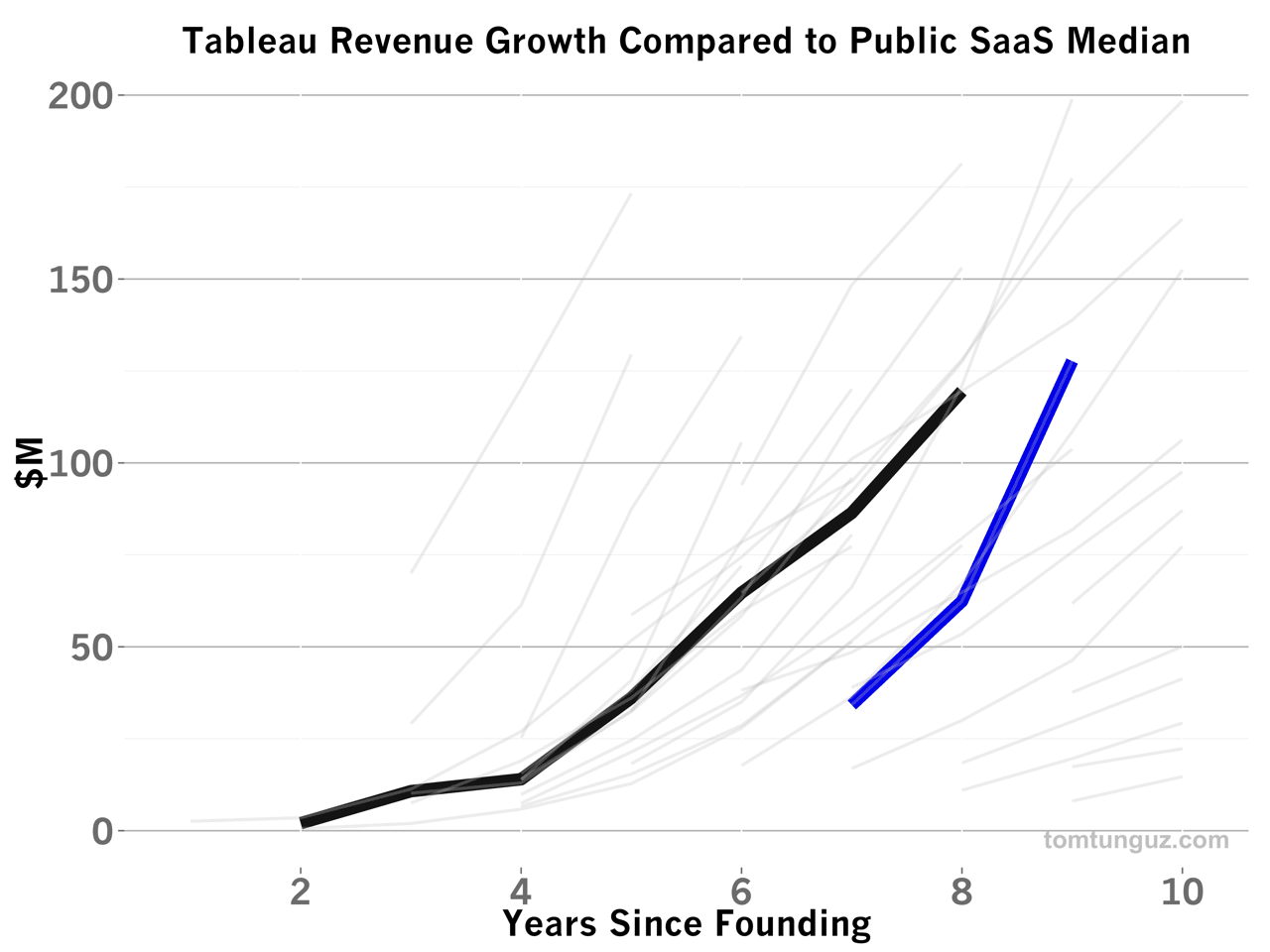

Founded in 2003, Tableau followed a more gradual revenue growth curve than the median SaaS company. But since the company hit its stride, about six years after founding, Tableau has been growing rapidly, recording a 94% CAGR for the last four years, and generating $232M of revenue in 2013. 70% of that revenue is one-time software license fees and 30% is recurring service and support. Tableau does sell a SaaS product (a hosted version of its desktop client), but the most recent quarterly reports indicate the revenue contribution is de minimus.

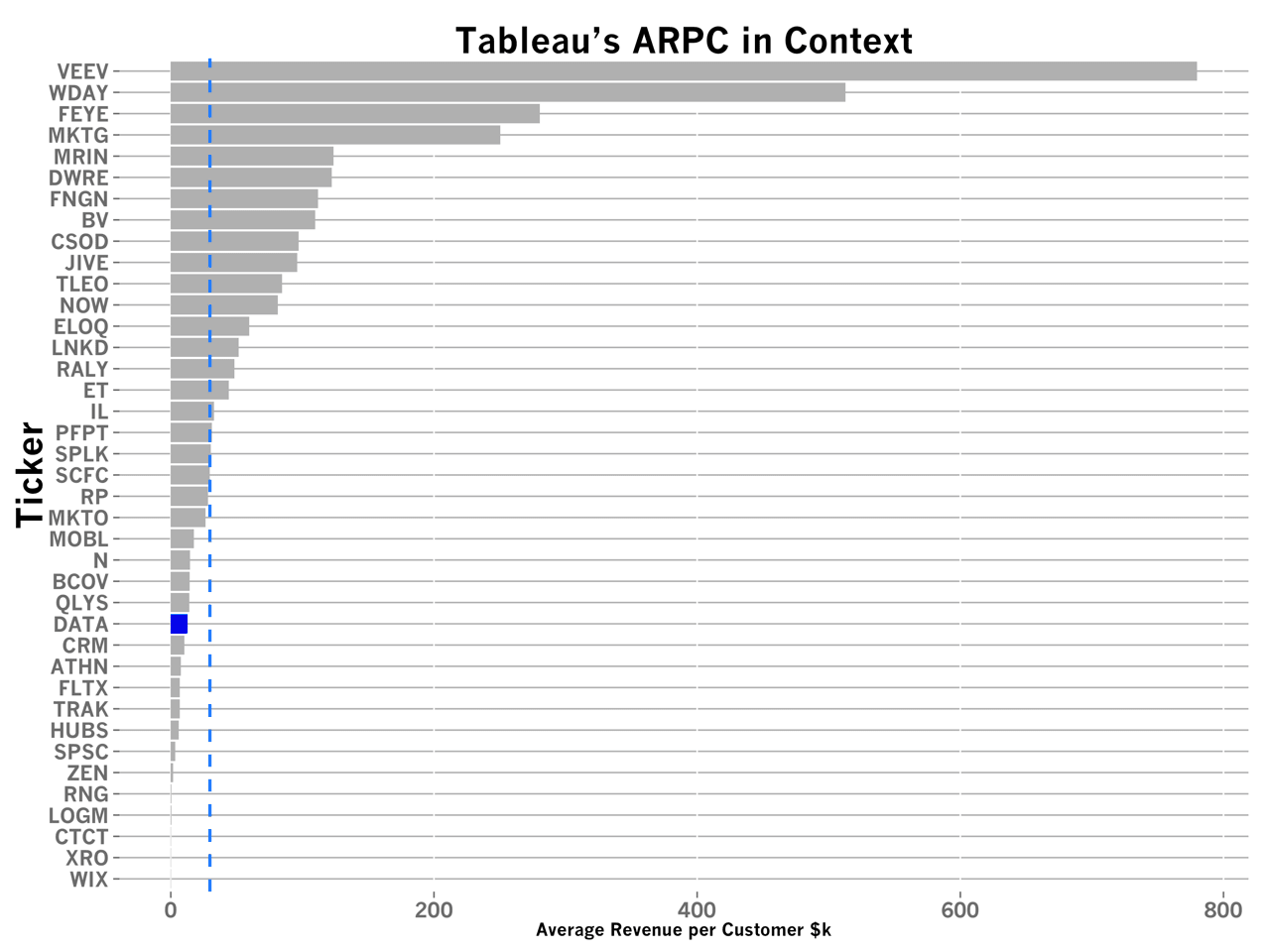

At IPO, Tableau’s average customer paid $12,773 for roughly six to seven seats. This average revenue per customer (ARPC) places the company in the 25% percentile for size of ARPC and below the median of $29k, indicated as the dashed blue line in the chart above. As mentioned above, these small initial deployments ultimately lead to much larger enterprise licenses measuring at least in the five figures and the pricing is part-and-parcel of the land and expand strategy.

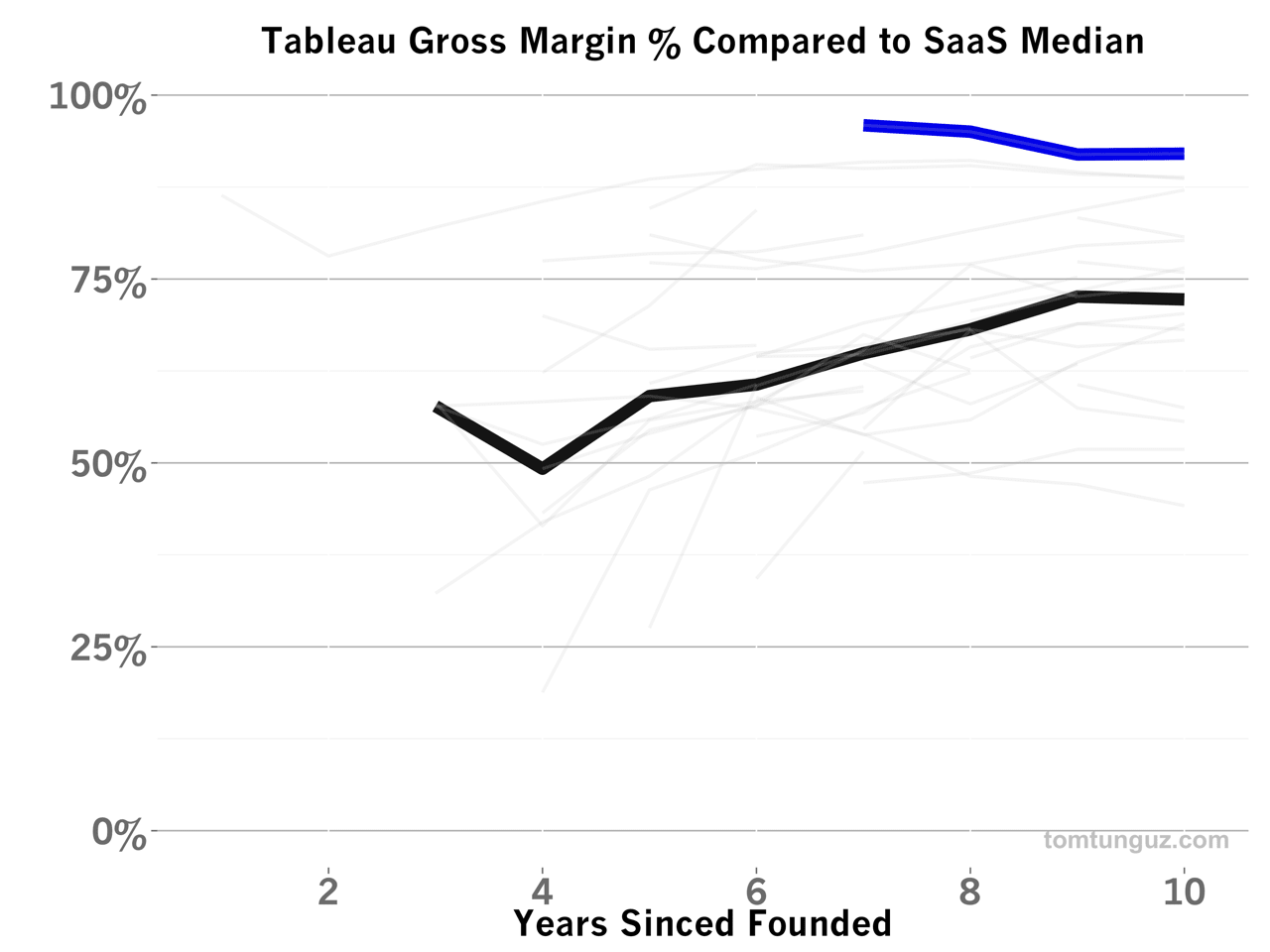

Tableau has the best gross margins of any company in the SaaS basket, 92%, compared to the median of 68%. Tableau’s margins are thirty-five percent better than the median SaaS publicly traded company for two reasons. First, Tableau’s software is sold as a client, an application users download to their machines and run in place, so there are no ongoing hosting or server costs. Second, customers pay for their own customer support and success as part of a typical deployment. Instead of contributing to the cost of revenue, customer success is a revenue line item.

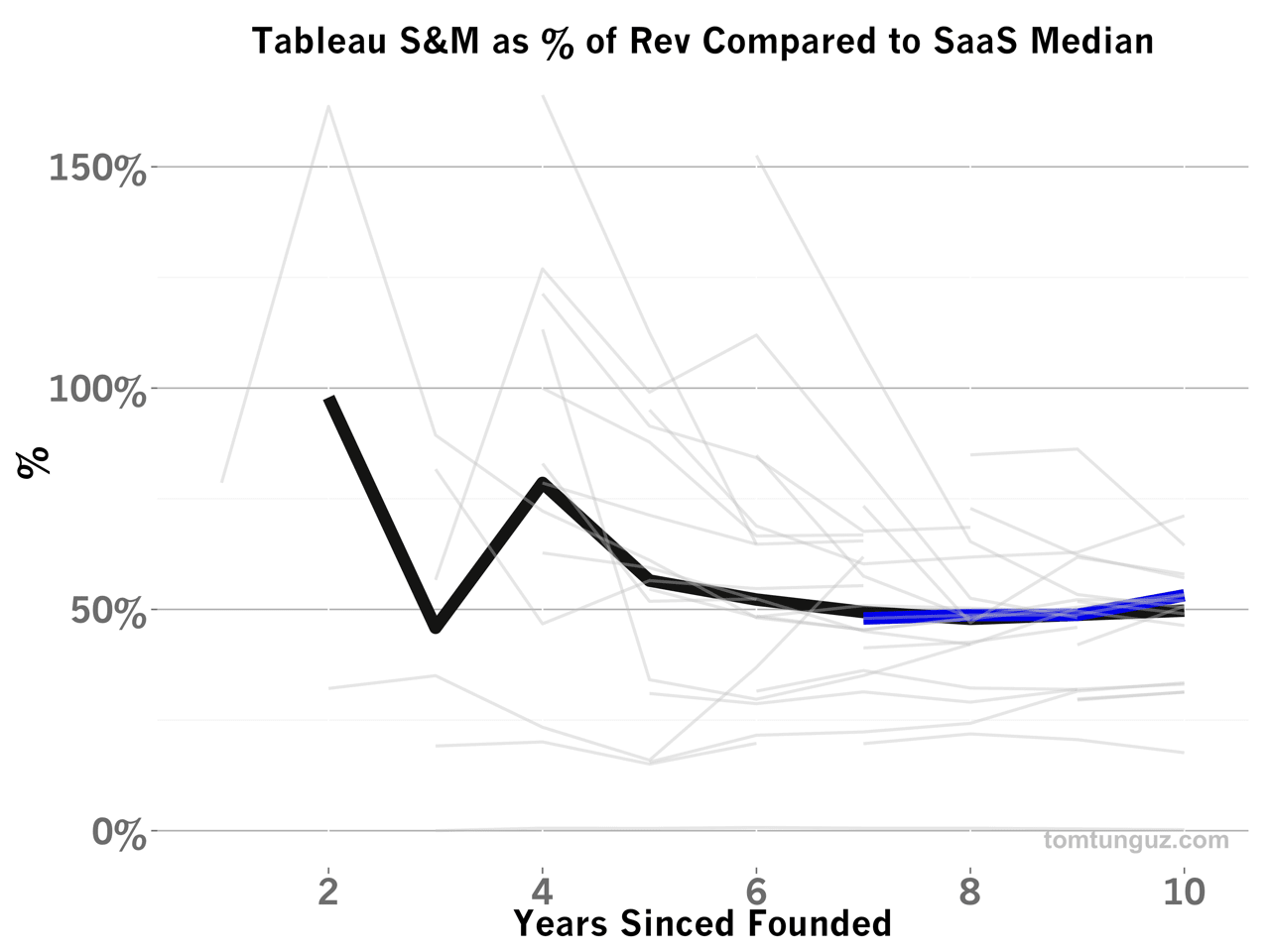

Tableau’s sales and marketing spend as a percentage of revenue traces the median at about 50%. While there is nothing special about this figure, there is about the next one.

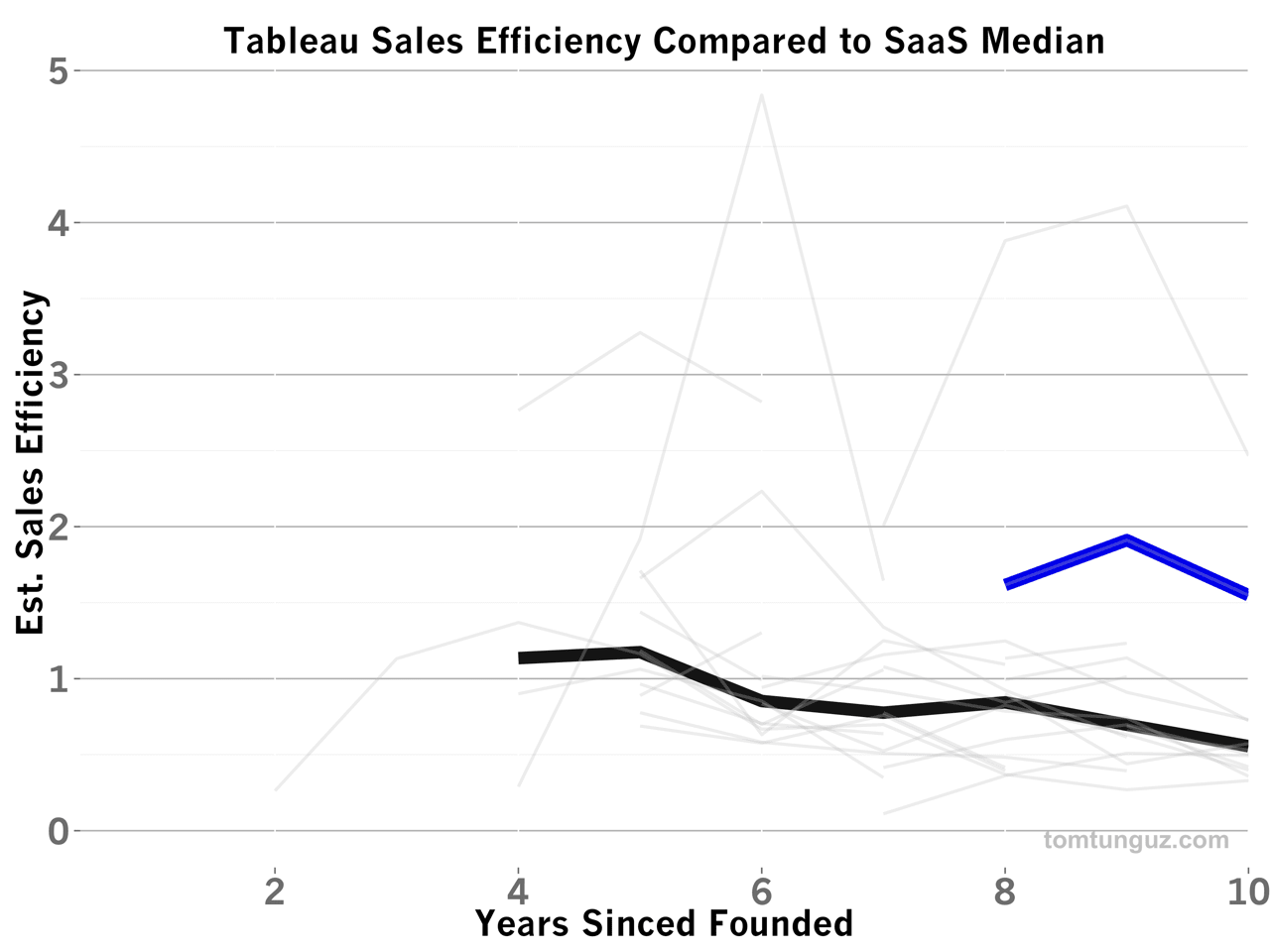

For every sales and marketing dollar Tableau invests, the business returns more than $1.54. Only LinkedIn and DealerTrak have better sales efficiencies for companies this “mature” (seven years or more since being founded).

Tableau achieves such terrific efficiencies by combining a freemium product with focused account expansion sales effort. Since the ultimate purpose of data analysis is to share insight, the software’s end product, data visualization, is often distributed broadly within its customers’ companies, engendering new interest which can be converted into account growth by the sales team.

Perhaps as a consequence of remarkable sales efficiency, Tableau has required very little capital to grow. The founders raised only $15M before taking the company public. At the end of 2012, six months before the company would trade publicly, the business counted $39.3M of cash on its balance sheet, meaning the business either hadn’t spent very much of the capital it raised or had spent it early and then replenished its cash balance with profits over time.

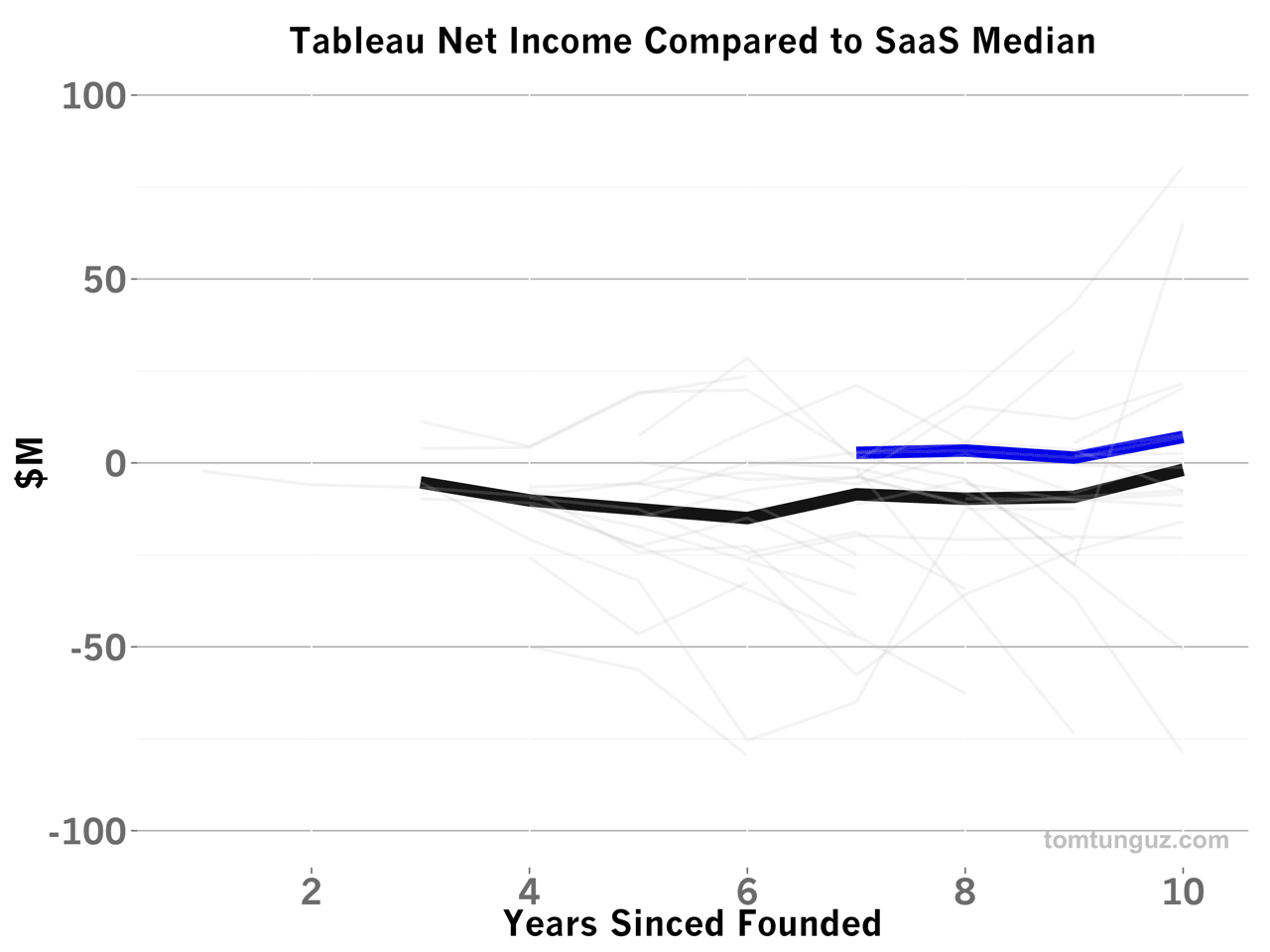

Since at least 2010, Tableau has been run profitably. In each of the years we have data on the business, the company never exceeded $8M in net income, and this is likely because the company plows all the potential profits back into customer acquisition and upsell.

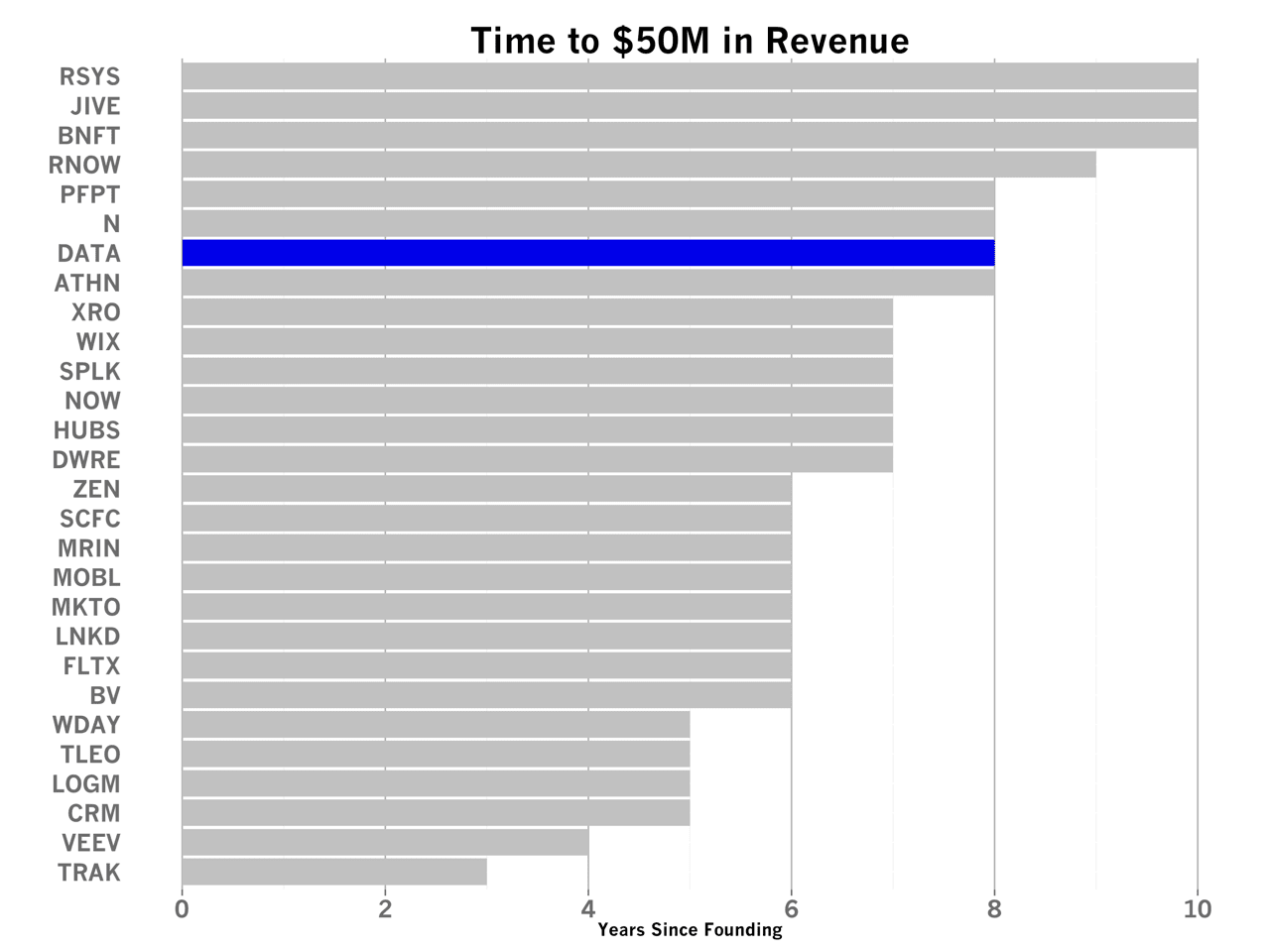

Tableau is among the slowest companies in the set above to reach the $50M revenue milestone, taking 8 years to exceed it. Tableau’s cash-conservative approach may have been necessary given the perpetual sales model. Tableau could count only on about 25% of their revenue to recur, the support and maintenance fees. Describing the business through a SaaS lens, one might say Tableau charges a higher upfront price than a SaaS product might, but suffers from roughly 10-11% monthly revenue churn. Managing this type of business is very different from today’s SaaS model, and the increased unpredictability of customer behavior likely demanded a more conservative operating plan.

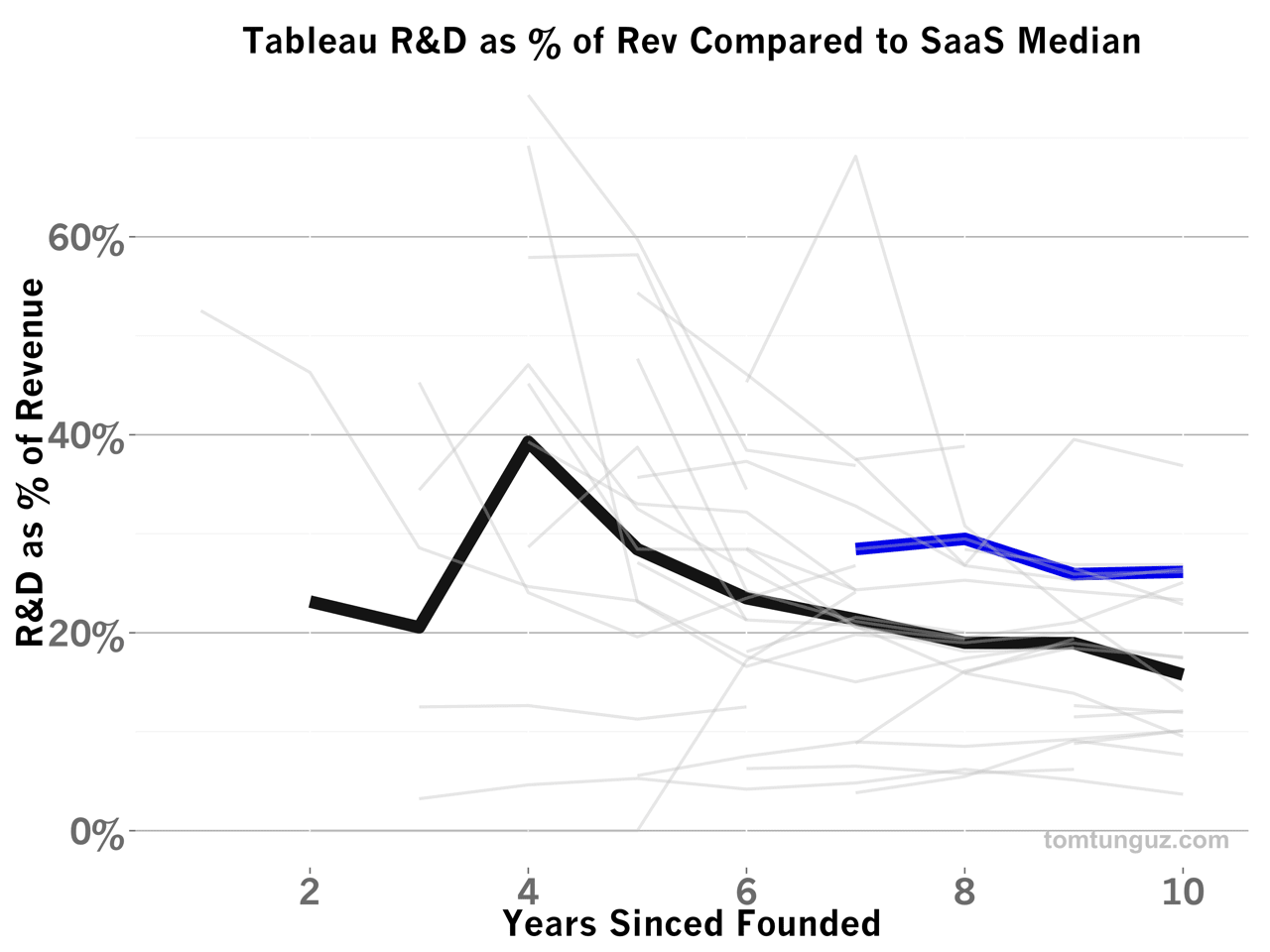

Tableau spends 26% of revenues on research and development, about 37% more than the median SaaS company. And they have been investing at this rate for as long as we have data to measure it. It may be that client software is more expensive to develop and maintain or that the footprint of the software is more expansive and requires greater development effort.

There is a tradeoff between the predictability of the SaaS business model and the margins of a perpetual license model. Tableau has been able to grow very much like a SaaS company, and arguably required less capital, though it has taken the business some more time to achieve the milestones and the company doesn’t benefit from the long-term revenue streams that subscription customers offer. As the company scales, I expect to see Tableau experiment with generating more consistent, and likely subscription revenue from existing customers either with subscription products, paid upgrades, more collaboration or other features.

Tableau is an impressive company for many reasons: terrific revenue growth, tremendous sales efficiency and a beautiful product. For founders it serves as a great role model for building a perpetual license business and a foil for the SaaS model of commonplace today.