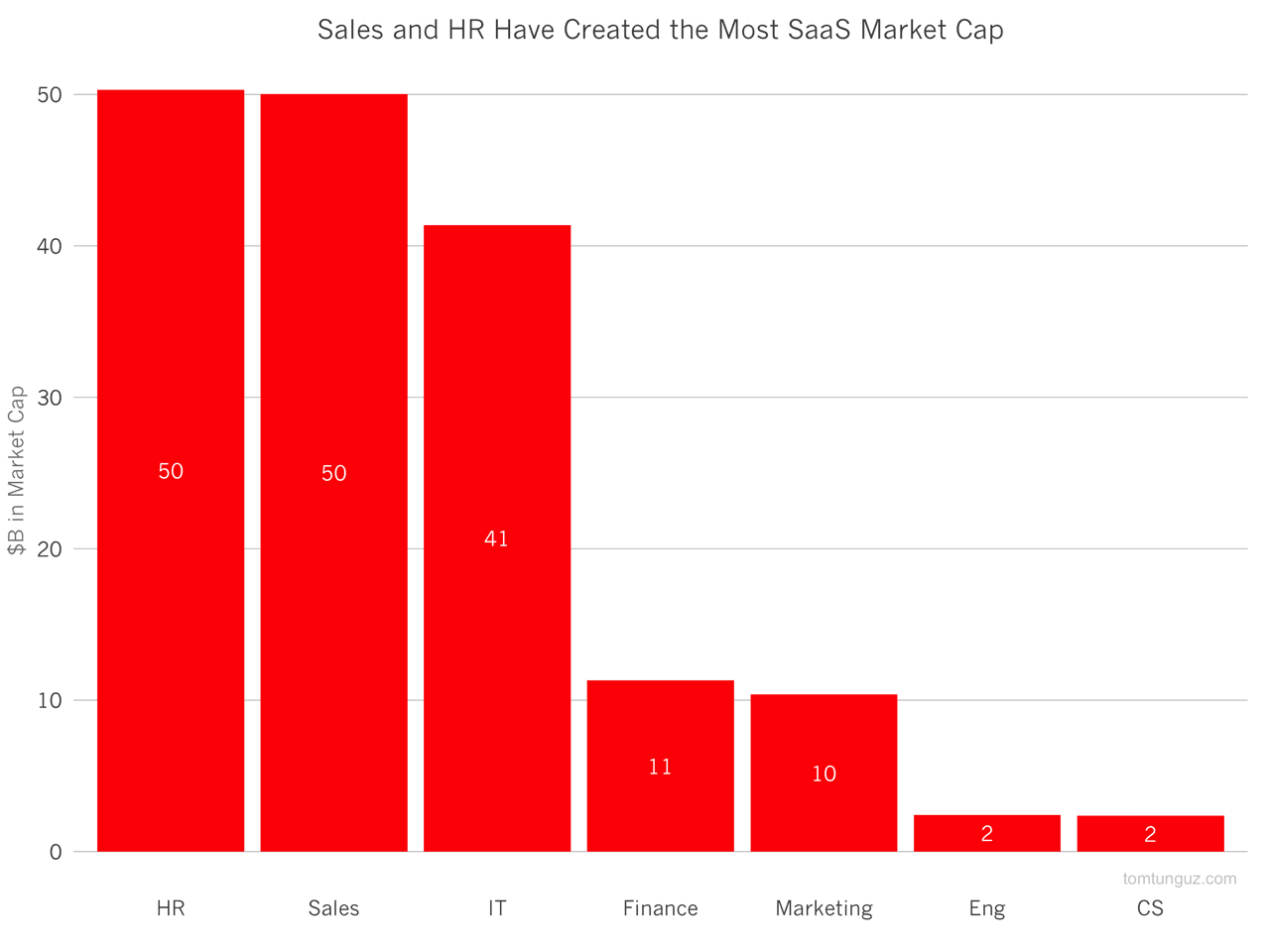

The Most Successful SaaS Sectors

In every sales process for every SaaS startup, there is one ultimate internal champion advocating the purchasing decision. And it’s their budget that will be used to pay for it. So, which departments within customers spend most on SaaS?

One way of looking at this question is to compare the successes of software companies targeting different departments. I have categorized the 50 or so publicly traded SaaS companies by their principal buyer, and tallied the aggregate market caps of those companies above.